|

Official Wetlands Press

Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Monday July 30, 2001

NYC's LEGENDARY WETLANDS PRESERVE ROCK CLUB FORCED TO CLOSE ITS DOORS

AFTER ALMOST 13 YEARS

New York, NY-- Landmark live music venue and activism center Wetlands

Preserve will be turning out its environmentally-friendly lights on

September 15th, 2001. After close to thirteen years at 161 Hudson

Street in TriBeCa, the gentrification of the Manhattan loft set has caught

up with the venerable club. The building is being sold and turned

into residential condos and the venue is being converted into office and

lobby space.

Since opening on Valentine's Day in 1989, Wetlands has become an

institution among musicians and fans, and has been frequently lauded for

its eclectic music programming. Wetlands has achieved national

prominence as the home of the burgeoning Jam Band scene through the

emergence of Dave Matthews Band, Phish, Blues Traveler, Widespread Panic,

Spin Doctors, and the many other improv-oriented rockers who performed

regularly at the venue in the 90s.

While serving as the "must play" venue for jam bands nationwide,

the club is also proud of its development of artists from a broad spectrum

of musical genres--Rock, Punk, Hardcore, Hip Hop, Reggae, Ska, Funk, Jazz

and electronic music. Some of the most prominent bands in

contemporary music were booked at the 500 person capacity club early in

their careers. For example, Pearl Jam, Sublime, Travis, David Gray,

Counting Crows, and Rage Against the Machine had their first NYC shows at

Wetlands. Oasis' first two shows in America took place at Wetlands.

"Wetlands is known worldwide as one of the most successful venues for

developing talent that the music industry has ever seen," said talent

agent Jonathan Levine of Monterey Peninsula Artists.

Konkrete Jungle, the first American weekly drum and bass party, called

Wetlands home for its first three years. And, just last year, The

Roots hosted a month long residency at the club that morphed into their

heralded weekly BlackLily party which featured an open-mic for female

talent, including Jill Scott, Macy Gray, and Erykah Badu. The club

has hosted numerous matinee shows on weekends, where the leading ska,

punk, and hardcore bands played scores of shows for packed audiences.

For the past several years, live electronica bands such as The Disco

Biscuits, The New Deal, Lake Trout and Sector 9 have also had numerous

sold out shows at Wetlands. The club was also the home of "Deadcenter",

which for ten years was the longest running and largest weekly gathering

of Grateful Dead fans in the country.

In an age where clubs are designed to cater to a niche demographic,

Wetlands welcomed everyone without the ego of a velvet rope at the

entrance. With a capacity of 500, Wetlands is the largest all ages

live music venue in New York City that is open every night of the week.

Wetlands has always encouraged the use of DJs before, between, and after

bands' sets to enhance the live music experience. While most clubs would

just have the sound engineer put on a CD between bands, Wetlands prides

itself on hiring a DJ for every show to accent the vibe of the evening.

Larry Bloch founded the club as a neighborhood watering hole for activists

and a center for environmental activity. Bloch's intention was to open a

club and to use revenue from the club, regardless of profits, to fund the

Activism Center at Wetlands Preserve, which is still a major part of the

club's operations. Since 1989, Wetlands has spent in excess of one million

dollars running the center, which is contained in-house and supports four

part-time employees as well as an army of volunteers and

interns who earn high school and college credit for their work at

Wetlands. The activism center works tirelessly on direct actions,

letter writing campaigns and petition drives to raise awareness of a

myriad of environmental and social justice issues. Every Tuesday since the

club opened, the downstairs lounge has been the host of Eco-Saloon

meetings. Each week features a different topic, and many nights have

featured special guest speakers (ranging from Timothy Leary and Allen

Ginsberg to Jello Biafra, Julia Butterfly, and William Kunstler), as well

as educators, activists, and indigenous people who would talk about issues

and share ideas of how to make the world a better place.

Some of the Wetlands Activism Center's more notable successes have

included lobbying successfully with the New York Times to get them to

cancel their contract with MacMillan Bloedel, a paper supplier who was

clear-cutting the Clayqout Sound, an old growth forest in British

Columbia.. They were also successful in persuading Home Depot, the largest

retailer of old growth rain forest wood, to cease the sale of wood from

environmentally sensitive areas by 2002.

"They don't make rock clubs like Wetlands anymore," says current

owner Peter Shapiro (who took control of the club in 1996). "Now it's

more about trendy lounges and carpeted live music venues. There's

something really special about going to the bathroom where the walls have

been graffitied and stickered on for 13 years, and where the bandroom has

seen nearly 20,000 guests over the years. There is a special feeling

in the air at Wetlands that is hard to describe, it's the kind of

thing that only happens after having shows every day for more than a

decade in the same room, and it's a feeling that very few other music

venues have." Shapiro adds, "At Wetlands, we tried to

create a kind of marriage between a neighborhood bar and a live concert

hall. A place where people come to meet, socialize with friends, and

dance to great

music."

Shapiro and the current Wetlands management team (including General

Manager Charley Ryan and Talent Buyer Jake Szufnarowski) plan on

continuing to use the Wetlands name to promote shows, and are looking for

a new space to call home in Manhattan. Recent Wetlands Presents shows have

included Sheryl Crow at Shine, as well as last month's Jammy Awards at

Roseland. Shapiro also produced the recent IMAX concert film ALL ACCESS.

Former Wetlands Talent Buyer Chris Zahn has rejoined the Wetlands team to

book some "special" shows featuring the club's alumni in the

club's final weeks at 161 Hudson Street.

For more information contact:

Jim Walsh

Coppertop PR

607-275-8217

*********************

From New York Magazine

Aug 3rd 2001 issue

Wetlands Sinks

By Logan Hill

"Damn! What are we going to do with the van?"

Twenty-eight-year-old club owner Pete Shaprio is distraught. He's just

discovered that the Wetlands Preserve, his thirteen-year-old jam-band club

and save-the-world hangout on Hudson Street, is falling victim to over

development, much like the spotted owls it once championed. The

shuttering of "the 'Lands" means the club's psychedelia-splattered,

activist-pamphleted VW bus must be towed from its stage-left parking spot

by mid-September. Then the building will be converted into luxury condos

and the club's hallowed hippie space on the ground floor - where floral

murals of Jerry Garcia and Santana still hang - will become office space:

from Deadhead to Dilbert. "We kind of knew it was coming," says

Shapiro, who recently produced the IMAX concert film All Access. "In

New York, the live-music venue is an endangered species."

Wetlands was pretty darn important," recalls Phish's Trey Anastasio,

who rode the crest of the jam-band craze starting in the eighties.

"If there was a scene, it kind of congealed there."

Now the "lands, which Blues Traveler's John Popper nicknamed

"Sweat Glands" because of its one-time lack of air-conditioning,

is closing - but Shapiro is already scouting real estate for another

activist club, a non-profit "Lincoln Center for rock music."

He's lined up support from enviro-friendly fashion designer Todd Oldham and

is in talks with Island Records founder Chris Blackwell. "We want it

to be huge," he says, "but you can't build another Wetlands - it

takes thirteen years to get that kind of graffiti."

Meanwhile, he's calling Wetlands vets like Dave Matthews and Rancid,

hoping they'll play in the club's last days. But he doesn't plan to follow

Twilo's lead and auction the van on eBay. "The "Lands isn't

really like that," he says. "We'll probably just give it to a

friend."

From New York Times

http://www.nytimes.com/2001/07/30/arts/music/30WETL.html

July 30, 2001

Vanishing Wetlands of the Musical Sort

By NEIL STRAUSS

Peter Shapiro knew the life of the club he owns, Wetlands, was drawing to

an end when he saw scaffolding and other signs of urban renewal slowly

working their way northward along Hudson Street in TriBeCa. Last week the

construction frenzy finally reached the doorstep of Wetlands, at the

corner of Laight Street, and the office building that houses it was sold

to an architect and a group of local residents who want to convert the

space into apartments. The club, which was on a short-term lease, is to

announce today that it will be closing in mid- September. For music fans,

already reeling from the loss of a number of clubs in a city whose

administration is seen as hostile to night life, the shuttering of

Wetlands, which opened in 1989, is a major blow.

"They called the other day to say they were closing their doors, and

I was devastated," said Marc Brownstein, the bass player in the electronica-fueled

jam band the Disco Biscuits. "I've been going to

the club since its opening, when I was in high school, to see this band

called the Authority. I was so amazed. It seemed like the biggest, most

prestigious venue in the country. When I got a band, our only goal in life

was to play Wetlands."

Nowadays the Disco Biscuits perform at far bigger clubs, like Irving Plaza

and Roseland, but they and scores of other bands credit Wetlands, which

holds 500 people, with nurturing them to national success. The club

remains best known as ground zero for post-Grateful Dead jam bands, and

the place that kick-started Blues Traveler, the Spin Doctors, Phish, the

Dave Matthews Band, Joan Osborne, and Hootie and the Blowfish. To

concertgoers, the name Wetlands evokes not just a room and a sound system,

but a wide-reaching genre of semi- improvisational music and a dedicated

audience of neo-hippies, who are often at the club as late as 5 a.m.,

watching the explorations taking place onstage.

For many of these late-night revelers, Wetlands is a way of life. Joe

Sarkis figures he has attended more than 900 shows at the club. "It

was my home," said Mr. Sarkis, known in the live-music world as

Concert Joe. He is best known for trying to get in the Guinness Book of

World Records for attending the most live-music shows in a single year

(though Guinness has yet to create such a category). When he hit his

1,000th show one year, Wetlands staff members prepared a ribbon outside,

which Mr. Sarkis broke as he entered the club to introduce the night's

performer, Jorma Kaukonen of Jefferson Airplane. "Most people get

thrown out of a club," Mr. Sarkis said. "Wetlands is the only

club that I ever got thrown into. They said that I had

paid more than anyone else to enter the club, and I didn't have to pay

anymore. I told them I was paying anyway, and two bouncers picked me up

and threw me in. Wetlands was the only place that ever let me in for

free."

In recent years the club has bred a new generation of jam bands, many of

which dip deeper than their predecessors into eclectic musical styles,

like bluegrass, electronica, funk and jazz. These bands include the Disco Biscuits,

Moe, the New Deal, Lake Trout, Sound Tribe Sector Nine, Soulive,

the Slip, Carl Denson, Deep Banana Blackout and String Cheese Incident. In

addition to jam- rock, however, Wetlands attracted other genres and their

cult followings, from hard- core rock to ska to hip-hop. Even Oasis, Pearl

Jam, Sublime, Rage Against the Machine, the Wallflowers and Counting Crows

all played their first New York shows there.

"People think of Wetlands as a new-hippie thing, but they did a lot

of hip-hop too," said Richard Nichols, who manages the rap act Roots.

"Other clubs are regimented and corporate, and Wetlands was way more

free-flowing and relaxed. It was actually one of the best sounding rooms

in the city."

Peter Moore, the architect who engineered the purchase of the building,

said he was trying to help the club find a new home, perhaps alongside a

youth hostel that is being built in a nonresidential neighborhood.

Speaking of the building's future residents, Mr. Moore said: "They

weren't going to buy the building unless Wetlands left. They go out to

clubs. They don't want to go to clubs within their own building."

In the ground-level corner of the building where Wetlands sits, an

engineer who designs microscope parts plans to open an office. So, Mr.

Moore said, the club has gone "from head banging to head

examining."

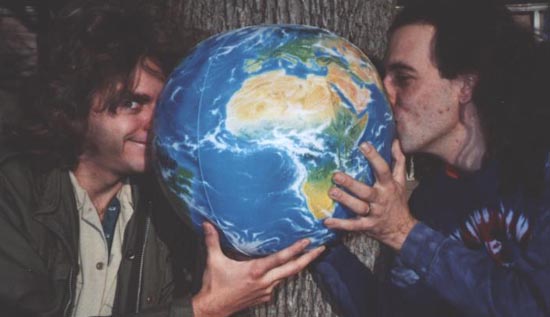

Wetlands was opened in February 1989 by Larry Bloch, who returned to

Manhattan after a decade in California to rear a family and, with no prior

experience, start a club. For eight years he created a tight knit family of

bands, fans, environmental advocates and loyal employees. In the mid-90's

he announced that he was leaving the world of night life to spend more

time with his son.

He spent nearly two years searching for a successor willing to carry the

environmental torch as well as maintain the musical legacy of Wetlands. He

found Mr. Shapiro, a freshly matriculated Northwestern film student with

absolutely no experience in running a bar or club. "I made it easy

for Peter," said Mr. Bloch from his home in Brattleboro, Vt., where

he owns an ecologically minded clothing store and activist center called

Save the Corporations. "He was young and naïve and idealistic. It

seemed more likely that somebody young like him would have a chance to learn

and become more

aware of the environmental and social conscience issues. Most of the

people wanted to buy the name and good will of Wetlands. They didn't want

to commit to what he committed to."

Among those commitments were to illuminate the club with only

energy-efficient light bulbs; use recycled paper for business cards and

stationery and in copy machines; allow groups like Greenpeace, Amnesty

International and the Rainforest Action Network to meet and recruit at the

club; and to have paid employees run the club's environmental center. Mr.

Shapiro had only just made his final payment for the club this month when

he discovered that he would have to close it. He said that he planned to

bring back some of the bands that made Wetlands famous (and that Wetlands

made famous) for a closing week blowout. Afterward, Mr. Shapiro; the

club's booker, Jake Szufnarowski; and longtime manager, Charley Ryan, will

be looking for a new Manhattan space, which they hope will house a bigger

and better Wetlands.

But as any promoter can tell you, with resistance from community boards

and city licensing authorities, opening a club in Manhattan is a

challenge. "It's a drag," said the guitarist Warren Haynes, a

club regular who has performed there with Gov't Mule and the Allman

Brothers Band. "It was such a friendly atmosphere, and we loved

playing there. I'm going to hate to see it go."

From New York Post

http://www.nypost.com/entertainment/36248.htm

MEMORIES FLOW AS WETLANDS DRIES UP

By DAN AQUILANTE

July 31, 2001 -- THE Wetlands Preserve is hard to find, the sightlines

inside are only fair, it is hot in the summer and hotter in the winter. It

is downright uncomfortable and has that faint odor of sweat and stale

beer.

The place, located on a desolate part of Hudson Street, is like a rock

roadhouse in upstate New York rather than one of Manhattan's intimate

clubs.

So why will New Yorkers miss it so much when it closes on Sept. 15?

"It had magic," said owner Pete Shapiro.

The Wetlands' flame was blown out by the winds of commerce and the

continuing gentrification of TriBeCa. The building's new owners are

planning to build condos, and will use Wetlands' street-level space to

make a lobby area and build offices.

It's an ironic end for this club, when you consider that making money was

never its primary objective.

"It had a special vibe about it because it was real," said

Shapiro, who was just 23 years old when he bought the Wetlands in '96.

"Every Tuesday, we got together for discussions and lectures at our

environmental center. We really did all of our printing on recycled paper.

We really did use the club's profits to try to make the world better.

"What we did at the club is see what could happen."

What could happen? He convinced Grateful Dead guitarist Bob Weir to invite

the boy rock band Hanson to jam there three years ago during the club's

10th anniversary celebration.

That show, which Shapiro recalls as one of the club's crowning moments,

"was what the club was about."

"Bob Weir and Hanson! It shouldn't have worked, it could have sucked

big time, but it didn't. It was great," Shapiro said. "We saw an

opportunity to see what could happen, and we took it."

Talking about the club's closing, Shapiro betrays a hint of denial that in

just over a month, the music is going to stop.

When asked if he had shed any tears, he just said, "I'm trying not to

think about it too much. You work in a club and you never have time to

stop. I'm trying not to stop, because I will start to think about it.

"The Wetlands is my life. It's part of me. My work and social life

are not separate. I don't want to think about what's going to happen after

our last show. That's when it's gonna hit me."

From Jam Base

http://www.jambase.com/headsup.asp?storyID=1363

7/30/01

GOODBYE WETLANDS

As a pragmatist, I know that loss is, in many cases, inevitable. It's

logical in the repetitive nature of things. As one cycle ends, another

begins and, if you dwell on the passage of it's predecessor, you lose

precious moments of your current experience. As a Gemini, I'm also very

sentimental. Although I wasn't there when the home I grew up in was sold

and all evidence of my childhood was removed, I wax on it now and again.

That episode has taken on greater significance as one of my current homes

is about to be emptied and changed to new owners who have decidedly different

intentions for the place.

As of September 15th, 161 Hudson St. will no longer rock as Wetlands

Preserve.

For thirteen years,

Wetlands has undergone it's own evolution, constantly

giving life to bands and activist energy. As a weekly meeting place for

the political and environmentally minded, Wetlands has always taken

serious account of it's responsibility to give back graciously instead of

merely sleeping off the party until the next one. That sense of heart has

also been evident to me in the staff and how they care for the place and

those that visit. From Kregg & Michelle at the front door, Lance &

Paulie on inside security, the bartenders, Jake doing booking &

promotions, Dave in the DJ booth to Peter Shapiro, the club's owner, and

everyone else in the cast that I didn't mention, the walls were made

softer not to accentuate the acoustics

in the air but those ruminating inside each person who came to have a good

time.

Most weeks, I spend more waking hours at Wetlands than I do in my own

apartment. The music comes with me wherever I go but it's not always

possible to provide myself the ample diversity that I can when I walk

through the doors of this venue. It's like having a live music changer

readily available any night. There's never just one band playing and

there's never just one type of music. Wetlands became famous for launching

such classic jam acts as Blues Traveller, Spin Doctors, Phish & Dave

Matthews Band but, all the same, the club has also hosted and developed

bands in every other area of musical creativity. Mostly, when such extreme

qualifiers are employed (like "every"), it's an exaggeration to

provide deeper emphasis. Not in this case, though. I challenge anyone to

find a form of music that hasn't been played there (well, maybe polka but

I wouldn't be surprised if that was there at some point, too). Wetlands

Preserve isn't just some house of eclecticism, it's a womb capable of

producing genealogies as diverse as the ingredients that have excited the

air from the lounge to the mainstage to the DJ booth.

Most recently, Wetlands has been a major force in the burgeoning

electronic movement. Through much of the club's life, it's rooms were

booked by Chris Zahn, who went on to manage The Disco Biscuits and is now

promoting various new bands. His position has been filled for the last

bunch of years by Jake Szufnarowski, whose dedication to the New Deal

helped the Toronto live breakbeat house band gain a large audience in this

area. Jake's strategies for placement are a direct representation of his

love for music and the game that's live. Within the house of diversity,

Jake's been the ringleader, helping to develop local/regional acts such as

ulu, RANA, Brothers Past and Soulive. He also brought in legends like

George Clinton, Ike Willis, Melvin Sparks and Dick Dale. I think one

recent episode characterizes Jake very well. Finnish surf metal band Laika

& the Cosmonauts were touring in the area and Jake's wide vision

caught this. Always on the lookout for a way to bring something special to

the stage, he made room for this band to play a set and give us a chance

to experience a band we definitely wouldn't have without Wetlands being

there. I'm lucky to have found a cherished friend in him who's also an

endless fount of inspiration.

The club's ethic also recently made the jump to the big screen through All

Access, the IMAX film made by the Shapiro brothers. While it visited other

stages, the idea of bringing different artists and styles to the people

was what it was all about. Many nights, anyone in the club could have the

opportunity to bend an elbow or just chat with one of the artists who'd

just performed. All Access brought the viewers behind the scenes and right

up on stage to get that same intimate feel that Peter and his staff

supported at Wetlands. The movie also flowed from one artist to another,

from Sting to Kid Rock, from Macy Gray to Moby and highlighted

combinations of new and old as it worked out with the teaming of Dave

Matthews Band and Al Green. Wetlands has been the NYC music scene's most

willing canvas, lending it's space to anything that any artist wanted to

be for that moment. From guest spots to all out open jams, the aura of

open possibility flows through the club's veins at a quickened pace.

There will be a noticeable hole in the scene as September cruises downhill

toward it's end. There will always be multiple somewheres to host the

music, whether it be in your mind or a more outwardly sheltered spot, but

character is subjective and the passing of Wetlands Preserve takes away a

unique being; a part of the family that's mother and sibling for everyone

who loves music. I had a conversation the other night with one of the many

musicians who filled that room with beautiful sound and we had a difficult

time thinking of any other venue in NYC that can step up closely to

helping the coming gap fill even partially. After almost eight years of

Rudy Napoliani's work on this city, the climate is very socially

conservative to the point that neighborhoods don't tolerate the noise and

traffic that a late night club generates. It will be tough to find a new

area willing to approve the zoning for the next incarnation of Wetlands

Preserve but that's not going to abate my hope that we'll all gather again

in an atmosphere created by the

same folks I so enjoy spending my time with now at 161 Hudson.

The next month and a half will not see the house of Preserve go down

quietly. The mainstage has been a spot of aspiration for many musicians

over the years so now it's just a matter of finding time for as many of

them as possible to make it back. As it stands now, plans are for the

bands to take us up to the last couple of days. The second to last will be

the ultimate jam session and the last day will be DJ Dave's chance to play

music recorded in the club over the years. I'll be there for as many

nights as possible over the next few weeks and take time off from work to

be there for all of the last two. If you're reading this, even if you're

not in the NYC area, come on down and experience a bit of history that has

nothing to do with souvenir plates, but everything to do with getting it

on.

As the streets get colder and my feet shuffle through the indications of

the changing seasons, my steps won't take me to that part of Tribeca

anymore. Every time I remember it's not there, the memories of Wetlands

will be a mix of joy and sadness but emotion is what births creativity,

just as it has at the club. It's nurtured thousands of bands and,

personally, has been my teacher. I've learned so much about so many

different ways to bring the music and now the pupil gets to push off from

that foundation and further find his way through the world, using the

lessons I've gathered. Luckily, the bands and the people associated with

Wetlands will also live on, all with the very positive pedigree of having

been a part of something that special.

There are countless things that can be said about Wetlands Preserve; what

it was, what it is and what it's closing means but I think what sums it up

best is a quote I heard at the club recently that I'll leave unnattributed:

"Fuck it. ROCK N ROLL!!!!" Howie Greenberg

JamBase NYC Correspondent

Go See Live Music!

Submissions are accepted by e-mailing headsup@jambase.com

Sunday New York Times

- Style Section

August 5, 2001

A NIGHT OUT WITH PETER SHAPIRO

Death of a Deadhead Dive

By ALEX BERENSON

THURSDAY, 11:45 p.m. at Wetlands, aka Wetlands Preserve, aka the TriBeCa

club that is closing Sept. 15 to make way for yet another set of

condominiums.

Blueground Undergrass, a six- man band from Atlanta, was about to play.

"Let's check out some tunes," Peter Shapiro said.

Mr. Shapiro, who bought Wetlands five years ago from the club's founder,

Larry Bloch, waded into the small but enthusiastic crowd in front of the

stage. As the lights darkened, he stepped forward in anticipation, beer in

hand. The band began to jam, and the crowd swayed in mellow synch to a

sound that was eerily like the Grateful Dead.

For 13 years, seven days a week, Wetlands has been a place for New York

music fans, kids from New Jersey and Long Island and overage hippies from all

over to listen to live bands of the kind that prefer extended jam

sessions to tight set lists or screaming guitars. With its battered bar

and

random Christmas lights, Wetlands has been a refuge from the moneyed

attitude of trendier boîtes like NV and Jet Lounge a few blocks north. At

this club for the neo-hippie set, patrons do not wear $700 distressed

jeans

or designer tie-dye. Just old jeans and T-shirts.

Perhaps 10,000 bands have played here, including Pearl Jam and Rage

Against the Machine. It may be the only club in the world with an "activism

center," where between sets, the young and idealistic can sign petitions to stop

global warming.

"It's been my life," said Mr. Shapiro, a scruffy blond who is a

big hugger.

Around 12:30, with Blueground Undergrass in full swing, Mr. Shapiro made

his way to the band room.

"This is where I like to hang out," he said, plopping down on a

worn,

aggressively ugly orange and gray couch. This colorfully dingy room

directly

behind the stage is covered with thousands of band stickers and obscure

graffiti that's piled up over the years. "Every night, it's like

throwing a

party," Mr. Shapiro said. He made his way back to the stage. About

100 fans stood out front, swaying, as the band launched into an extended jam with

Mike Gordon, the bass player from Phish. A couple of marijuana pipes

worked their way through the crowd. One was offered to Mr. Shapiro. He declined.

The nights blur together, Mr. Shapiro said, good and bad, though a few

stand out. On the club's 10th anniversary, Bob Weir, of the Grateful Dead,

played with the Hanson brothers. At 1:30 a.m., Mr. Shapiro was keeping the party

alive. "More shots," he yelled, corralling employees, who

gathered for a toast to the club.

Then Blueground Undergrass took a break, and some of the audience filed

into the night. Mr. Shapiro left with them. He still had one more club to

visit.

This club is very new. It does not yet exist. A developer planning to put

up

a commercial building on a parking lot a few blocks from Wetlands has

asked Mr. Shapiro to help create a 1,500-person venue for live shows.

Of course, community boards must be appeased and financing arranged at a time

when finance is increasingly scarce. The odds are long. But Mr.

Shapiro has faith.

"I could see in my head the stage right here," he said, leaning

against the

chain-link fence protecting the lot. The new club will be big and modern,

but suffused with the same gentle energy that filled Wetlands. Bob Dylan

for

four nights, intimate shows with artists like Sheryl Crow.

"This is my dream," he said, looking at the delivery trucks

parked silently

on the asphalt. "To take the spirit of what that place is and take it

to the

next level."

Saturday New York Times AUG

04, 2001

Now Playing in Clubland: Hard Times

By MIREYA NAVARRO

When Wetlands, a TriBeCa club famous for

fostering the careers of quirky bands, announced this week that it was

closing, music fans were devastated, but those in the industry were hardly

surprised.

The building on Hudson Street that houses the

club was sold to a group that wants to convert the space into apartments,

and Wetlands and its late-night revelers didn't exactly fit into its

plans.

To club owners, it is a familiar situation. They

say it has become harder for nightclubs to survive in New York because of

steeply rising rents and changes in zoning that have allowed residents to

move into areas that used to be the preserve of industry and business.

With residential neighbors abhorring the same

things clubs covet — crowds, traffic, noise — and with community

boards exerting considerable influence on state and city licensing

agencies these days, many areas of the city, especially downtown, are now

virtually off limits. Other areas are willing to accept only clubs that

open in existing nightclub space, owners say.

"This is the toughest atmosphere for

nightclubs in New York since Prohibition," said Robert Bookman, the

lawyer for the New York Nightlife Association, a group representing about

100 nightclubs.

The city's Department of Consumer Affairs, which

issues cabaret licenses, says that 319 establishments hold licenses this

year, including nightclubs, strip clubs and other businesses with dancing,

like restaurants, down from 333 last year.

Club owners say what is more telling is that

fewer businesses even make it to the licensing stage because of the

difficulties of finding a location. They note that the number of clubs

remained virtually flat in recent years while the city itself was in a

long period of economic growth.

But if the nightclub industry is looking for

sympathy, it will be hard pressed to find any in the city, where

quality-of-life issues became one of the hallmarks of the Giuliani

administration.

The association of nightclubs said business

became trickier in the early 1990's, when new city and state legislation

made it harder for a club to obtain a cabaret license for dancing or a

state liquor license. One law has also empowered the local community

boards to reject a club that wants to open within 500 feet of three

existing businesses that serve liquor.

"Residents and clubs just don't mix,"

said Madelyn Wils, the chairwoman of Community Board 1 in Lower Manhattan,

which has successfully fought the openings of clubs. "Nine out of 10

times there are problems."

The Copacabana, the granddaddy of dance clubs in

the city, exemplifies the struggle that club owners say is driving some of

them away or out of business. In many ways, the Copacabana is in a

category of its own. It has operated since 1940 (with a three-year hiatus

in the 1970's after its original owner died) in a business where 5 to 10

years is considered a healthy life span. And it has served up the same

music for the past 20 years — salsa and merengue — in an industry that

caters to the latest fad.

But this year, the Copa became just another club

pitted against the realities of the city's real estate market. Its rather

unglamorous neighborhood of car dealerships and parking lots near the

Hudson River suddenly became more economically desirable. So after nine

years on a block of low buildings on West 57th Street, the club was forced

to move out last month to make way for two new office towers.

John Juliano, who owns the Copa with two

partners, said the search for a new home started about a year and a half

ago after he was notified by the property's new landlord that the club's

10-year lease would be terminated early. The owners looked at more than 50

locations in spaces ranging from parking lots to the former Studio 54,

which was tied up with the musical "Cabaret."

The search was restricted not only by residential

encroachment, but also by the club's needs. The owners wanted at least

25,000 square feet. After holding 10-year leases at two previous

locations, this time they wanted a lease no shorter than 25 years. They

settled for a 47,000- square-foot building at 570 West 34th Street, near

11th Avenue, that used to house offices. The Copacabana will reopen at the

new site next summer. In the meantime, it has moved its live music to

another club, Ohm, on West 22nd Street, four nights a week.

"It's been a nightmare," said Glee

Ballard, the Copa's general manager. "The biggest problem is that you

have to go to an area available for a cabaret and a liquor license and

then you want a wide open space." She said that the new spot, at a

rent at least five times as high as the old site's, is in an industrial

area where the club "can't annoy anybody."

"There's no such thing as going to

prestigious neighborhoods," she said. "You can go there with a

McDonald's or a big department store, but clubs, no. Everybody acts as if

entertainment is not desirable."

Deputy Police Commissioner Thomas Antenen, the

department's chief spokesman, said both the police and residents had

become less tolerant of problems associated with clubs. "It's not so

much what happens in the clubs," he said, "but the stuff that

happens in the immediate areas: fights, people hanging out, making noise,

maybe drinking."

Marty Arret, owner of the Latin Quarter on the

Upper West Side, said that in his neighborhood, gentrification had drawn

neighbors who opposed his club. The club, at one time known as Club

Broadway, has a mostly Hispanic clientele and has been at the same spot

for 20 years.

"They call us and say, `Why don't you go to

the Bronx?' " he said.

As it turns out, the Latin Quarter is shutting

down on Aug. 31; its landlord decided to rent the space, on Broadway near

West 96th Street, to a bank. Mr. Arret said he was looking for a new

location but had found that most available places were going for at least

double his current monthly rent of $25,000.

David Rabin, who is the president of the New York

Nightlife Association and an owner of Lotus, a supper club, said it took

him three years to find a site for the club. Lotus opened about two years

ago in a former strip club on West 14th Street, in the meatpacking

district in Manhattan. Since then, he said, rents per square foot have

more than tripled in what used to be "a block full of prostitutes and

meatpackers."

Mr. Rabin said he spent $5,000 a week on security

and faced constant police inspections. He said he was pursuing his next

business deal in Las Vegas.

Kathryn E. Freed, a city councilwoman who

represents Lower Manhattan and has been a plaintiff in court cases against

several clubs, played down the clubs' concerns. She said clubs and

residential neighbors coexisted peacefully in many parts of the city,

usually because the clubs had made an effort to minimize any disturbance

to the neighborhood. "Night life doesn't have to be disruptive,"

she said.

Ms. Freed said there was still room for

improvement. She said she favored tightening noise regulations and

requiring waiting areas inside the clubs to eliminate the velvet rope

crowds outside.

Neighbors like Ms. Wils say noise is not the only

problem; they cite alcohol, drugs, lewd behavior and sometimes even

shootings outside the clubs. In New York, as in other areas of the

country, the rising popularity of Ecstasy and other illegal drugs has

drawn a police crackdown.

Police officials said that in the past year and a

half they had sought to close at least five major clubs for allowing the

sale and use of so-called designer drugs on and around their premises.

George A. Grasso, deputy police commissioner for legal matters, called the

problem a continuing concern, but said it was not necessarily worse than

in past years.

Club owners concede there are bad apples among

them, but say the clubs need more police presence. In 1999, the nightclub

association asked to hire off-duty uniformed police officers, as clubs do

in other cities, but the Police Department declined. In a letter to the

group, the department said the proposal was not "legally

permissible" and could expose the city to "substantial

additional risk of civil liability."

Mr. Bookman, the lawyer for the nightclub

association, said the city's world-famous reputation for night life was

bound to erode unless zoning variances were reined in, the police helped

out and there was "respect for the industry as a taxpaying

industry." According to a study by the night life association, the

industry funnels close to $3 billion a year into the city's economy.

Mr. Juliano at the Copa said he regretted not

having bought a building years ago. Now, he said, it would take $10

million to buy one and $5 million to renovate it.

Even for the Copa, that is out of the question,

he said. "Just don't have the money."

|